Click HERE to see the CDC recommendation for RSV vaccination for adults

You are about to leave a GSK website

You are about to leave a GSK website. By clicking this link, you will be taken to a website that is independent from GSK. The site you are linking to is not controlled or endorsed by GSK and GSK is not responsible for its content.

RECOGNIZE THE THREAT OF SEVERE RSV

RSV can come with serious and even life-threatening risks for certain adult patients1

Each year in the United States, approximately 177,000 adults aged 65 years or older are hospitalized, and approximately 14,000 of them die from RSV infection.1

In a retrospective chart review of adults hospitalized with a diagnosis of RSV,

26

of 109 adults aged ≥65 years were admitted to the ICU2*

- *

A retrospective chart review was conducted where 132 physicians supplied 379 patient cases of adults aged ≥18 years hospitalized with a diagnosis of RSV from October 2014-October 2016 to report the burden of RSV infection in adults during and post-hospitalization. Patients were classified as 1) immunocompromised; 2) having a comorbid lung disease; 3) aged ≥65 years not included in the first two categories; 4) all other adults. Relatedness to RSV for the reason for hospitalization was categorized by the treating physician. Among all patient cases, significantly more patients in the ICU had suspected bacterial co-infections compared with non-ICU patients.2

In another study, 13.4% of adults aged 60 years and older hospitalized with RSV had an in-hospital outcome of invasive mechanical ventilation or death (n=299)3†‡

- †

Data from a prospective cohort study conducted from February 2022-May 2023 that described RSV disease severity in hospitalized adults within the Investigating Respiratory Viruses in the Acutely Ill (IVY) Network.3

- ‡

In-hospital outcome was based on clinical data beginning at initial hospital presentation and ending at the earliest of hospital discharge, patient death, or end of hospital day 28.3

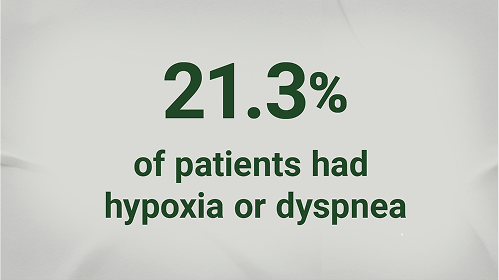

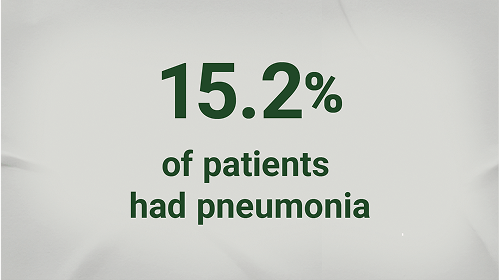

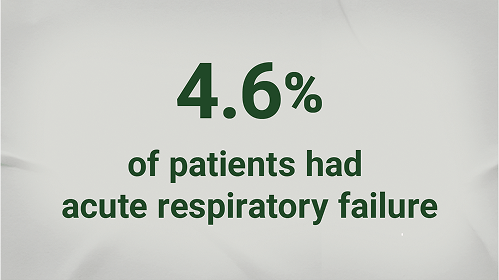

In a study, among 40,525 patients aged ≥60 years with a diagnosis of RSV and without any baseline RSV-related complication4§:

- §

A retrospective, longitudinal cohort study of Medicare claims from 2007-2019 of adults aged ≥60 years (N=175,392) with at least one claim with a diagnosis code for RSV described the proportion of patients that experienced RSV-related complications. The observation period for complications spanned through the earliest of 6 months following the index date (date of first claim with diagnosis code for RSV), the end of continuous health plan coverage, or the end of data availability. Patients were considered not to have a baseline RSV-related complication if there were no claims for the complication 6 months before the index date. The mean (median) time to first RSV-related complication for hypoxia/dyspnea, pneumonia, and acute respiratory failure ranged from 1.0 (0.2) to 1.4 (0.4) months.

RSV can exacerbate certain underlying conditions5

ICU=intensive care unit; RSV=respiratory syncytial virus.

References

Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1749-1759. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043951

Walsh E, Lee N, Sander I, et al. RSV-associated hospitalization in adults in the USA: a retrospective chart review investigating burden, management strategies, and outcomes. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5(3)e556. doi:10.1002/hsr2.556

Surie D, Yuengling KA, DeCuir J, et al; Investigating Respiratory Viruses in the Acutely Ill (IVY) Network. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus vs COVID-19 and influenza among hospitalized US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e244954. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.4954

DeMartino JK, Lafeuille M-H, Emond B, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-related complications and healthcare costs among a Medicare-insured population in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(5):ofad203. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad203

Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV). RSV in adults. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/adults/